In the past decade, countless books have been published about the Taliban, examining its origin, ideology and goals. But few authors or experts have told us anything new. And much of what is said about this Islamic student movement and its role in Afghan politics is one-dimensional. The Taliban’s aesthetic, for instance, is almost completely absent from the current literature.

Poetry of the Taliban well and truly makes up for this shortfall. The editors are scholars who have spent considerable time among Pashtuns of Kandahar, and were responsible for the sensational biography My Life with the Taliban by Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef. This time they give us a unique anthology of Taliban verse.

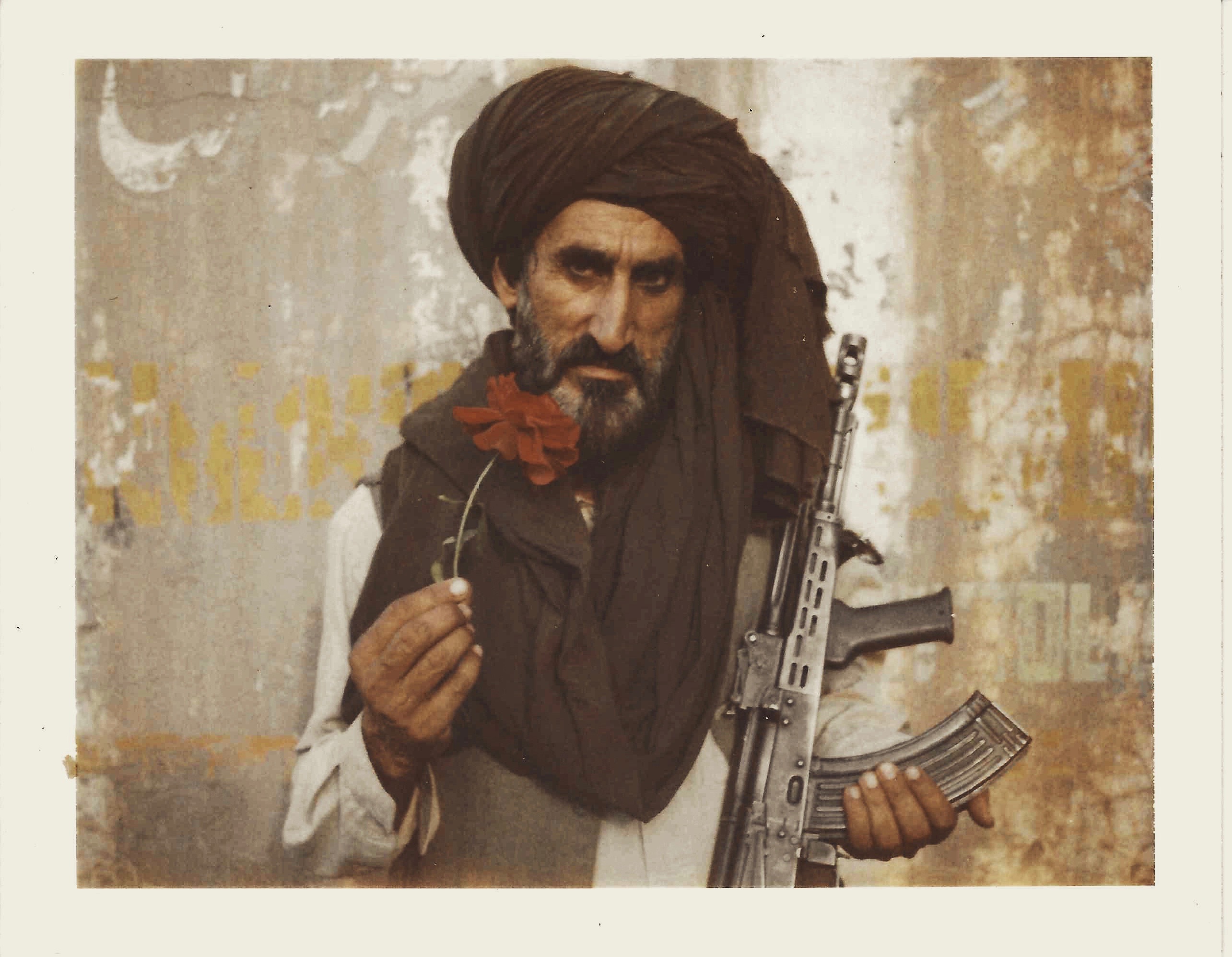

The notion of poetry produced by fierce and merciless men apparently opposed to singing and dancing is, at first, difficult to grasp. The title Poetry of the Taliban is bound to confound many who buy into the traditional stereotypes of our ”enemy”. But the collection is a complete surprise. The editors have compiled poetry found on the Taliban’s official website and in pamphlets or MP3 format, sometimes used in the place of ringtones. Almost all the poems in this volume are translated from the Pashto language, and include verse from the mid-’90s (when the movement first began) to the present day. While much of the world sees the Taliban as religious radicals and rigid conservatives, this anthology is full of beauty, tenderness and fine emotions laid bare. It fits well with my own experience of Afghans in Herat, where burly, bearded men in roughly tied turbans reclined by the Blue Mosque, enjoying the scent of freshly cut roses held in their hands.

So there are plenty of love poems among those with religious and nationalist themes. But the most common subject, as expected, is the suffering precipitated by conflict and the ongoing occupation of Afghanistan.

You would not ask me what happened

to the small congregation:

The grey and dusty mosque,

The one in the middle of the village,

The pretty mosque without a door.

And the tender Talib Jaan,

The one with long hair,

The young Talib Jaan,

Who used to cleanse hearts with his voice

when he called azan.

Any good intentions the international community may have for helping Afghanistan are meaningless to the Afghan man who has lost his children to the conflict, or the Afghan woman who has lost her husband.

Indeed, there are even poems from women belonging to the Taliban, such as the warrior poetess known only as Nasrat.

Give me your Turban and take my veil,

Give me the sword so that the matter will be dealt with.

Poetry distils events into simple terms. The violence with which foreign armies carry out their objectives has provided Taliban poets with fertile material for convincing Afghans that this war is about ordinary people fighting to protect their home, their faith and their simple way of life.

We love these dusty and muddy houses;

We love the dusty deserts of this country.

But the enemy has stolen their light;

We love these wounded black mountains.

Part of our reason for being in Afghanistan, we’re told, is to promote human rights by freeing the people from a harsh Taliban theocracy. But this collection is packed with outrage at the atrocities committed by the occupiers themselves. Indeed, there are frequent references throughout to the hypocrisy of the foreigners.

A flood of blood came here.

Black calamities wandered in the sky;

The young bride was killed here,

The groom and his dreams were martyred here.

A story full of love was martyred here.

But the press release from Bagram says,

‘We have killed the terrorists today.’

Already, this anthology has caused considerable controversy in Britain, where Richard Kemp, the former commander of British forces in Afghanistan, accused the publishers of reproducing ”self-justifying propaganda”.

It’s easy to ignore the important role poetry and proverbs play in Afghan daily life by dismissing this book as pure propaganda. But even if it were, what is tribal poetry up against US propaganda, such as the recently screened $20 million feature film Act of Valor?

As the coalition prepares to withdraw from Afghanistan, getting to know the enemy through their poetry might seem too little, too late. But Julia Gillard’s comments would indicate that Australia’s aid commitment to the country will continue long past 2013. Now is as good a time as ever to try to understand the people with whom we are dealing.

POETRY OF THE TALIBAN

Edited by Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn

Hurst, 247pp, $31.99