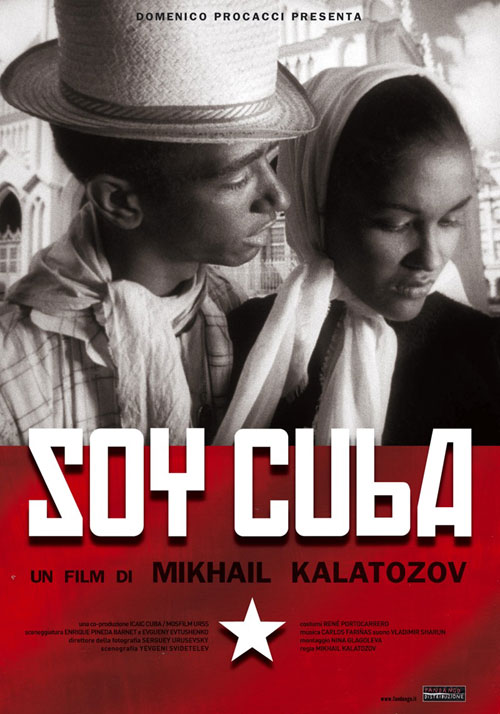

On a balmy night last month, a guitarist friend of mine, Carlos, was due to perform with his vocalist girlfriend and a man on congas at the Hotel Capri in Havana. Earlier in the day I’d promised Carlos I would drop by and see him play. Since arriving in Cuba on holiday I’d been meaning to check out the renovated Hotel Capri anyway. It had been on the top of my list of places to visit from the time I first saw one of my favourite films, ‘Soy Cuba’, or in English, ‘I am Cuba’.

At the beginning of the film, a canoe glides past river-dwelling Cubans going about their day in a chrome-like brightness, the action suddenly jumping to a lavish party on the rooftop of Havana’s splendid Hotel Capri. The first extended tracking shot at the Capri is arguably one of the most stunning in the history of cinema. Along with the close-up wide-angle lenses and the Soviet military infrared film stock used, the cinematography of this Russian/Cuban co-production is breathtaking. While ‘I am Cuba’ may not have been well-received at the time, with the help of American director Martin Scorsese it was restored in the 1990s and has since gain a cult following.

But it was not ‘I am Cuba‘ that made Hotel Capri famous. There is a reason the hotel was featured in ‘The Godfather: Part II’ in which it was signed over to the Corleone family. When the Capri opened in 1956, guests were personally greeted by actor and real-life mobster George Raft. Indeed, the Capri is said to have been financed by the US Mafia Syndicate, including such colorful characters as Charles Turin (aka ‘The Blade’) and Santino Masselli (alias ‘Sonny the Butcher’). With it’s hedonistic pool parties attended by the likes of actor Errol Flynn, a busy casino and cabaret hosting Liberace and Tony Martin, Hotel Capri was considered by Cubans to be the headquarters of American capitalist decadence. But it was a short-lived heyday that ended with the revolution less than four years later, in 1959.

Until the late 1990s the Capri was being managed as a modest state-run hotel that could only have been described as 2-star until it finally fell into total disrepair and closed fifteen years ago. In January this year it re-opened after a full restoration, run by government-owned company Grupo Caribe and Spanish hotel chain NH Hoteles SA, an unimaginative lot, as I soon discovered.

The anticipation of experiencing this resurrected historical icon excited me as my battered turquoise ’58 Chevrolet taxi spluttered down the Malecon. On arrival I noticed the exterior signage, that classic deco logo, was encouragingly intact. From the outside at least the hotel appeared unchanged. But as I entered the foyer, my heart sank. This was the lobby into which a hundred revolutionary soldiers swarmed one night in 1959 while George Raft was up in his penthouse entertaining the newly-crowned Miss Cuba. Now, apart from original brass chandeliers, the place could have been the lobby of any Hilton or Marriott. Plain, cream lounges and square ottomans, black and grey walls, white marble floors. It was sterile, soulless.

At the front desk I perused photos of the room options. All of them seemed done in the same olive green and yellow and what could have been Ikea furniture. It was strange to be given a choice, as each characterless modern room seemed indistinguishable from the next or, for that matter, from any other room at your average Holiday Inn. I shook my head in disgust and took the lift to the rooftop restaurant which used to be George Raft’s penthouse. It was now a mishmash of tacky decor, deep purple walls, black chairs with purple upholstery, and purple chiffon curtains. It was as if I had by accident wandered into the dining room of a recently-built nursing home. And it was in this restaurant that my friend Carlos, one of the most incredible guitarists I know, along with his singer and percussionist, played to a single male guest dining on a chicken steak.

Carlos was mid-song, so I gave him a nod and went over to the purple chiffon curtains of the restaurant that overlooked the famous rooftop pool in which a water-ballet of beautiful bodies once cavorted so delightfully in the opening scenes of ‘I am Cuba’. It now lay empty, surrounded by molded plastic banana chairs, circa 2003. The only recognizable remnant of the era was the sculpted fifties concrete poolside shade area. Through the window I could hear the doof-doof of bad techno and together with the cheap flashing neon lights it seemed like a helpless invitation to a party run by a host without a semblance of style or spirit, let alone nostalgia.

After saying goodnight to my friends I took a taxi back home, somewhat melancholy, as I often feel when the romantic notions of the past are obliterated by the now. In the last few years Cuba has been feverishly restoring it’s crumbling architecture, many with financial help from UNESCO. Let’s hope the Cuban interpretation of modern restoration doesn’t decimate more of the heritage it is supposed to be salvaging. Restoration is all too often mistaken for modernization at the expense of bringing buildings back to their ‘former glory’. Unfortunately for the Hotel Capri, it may be too late.