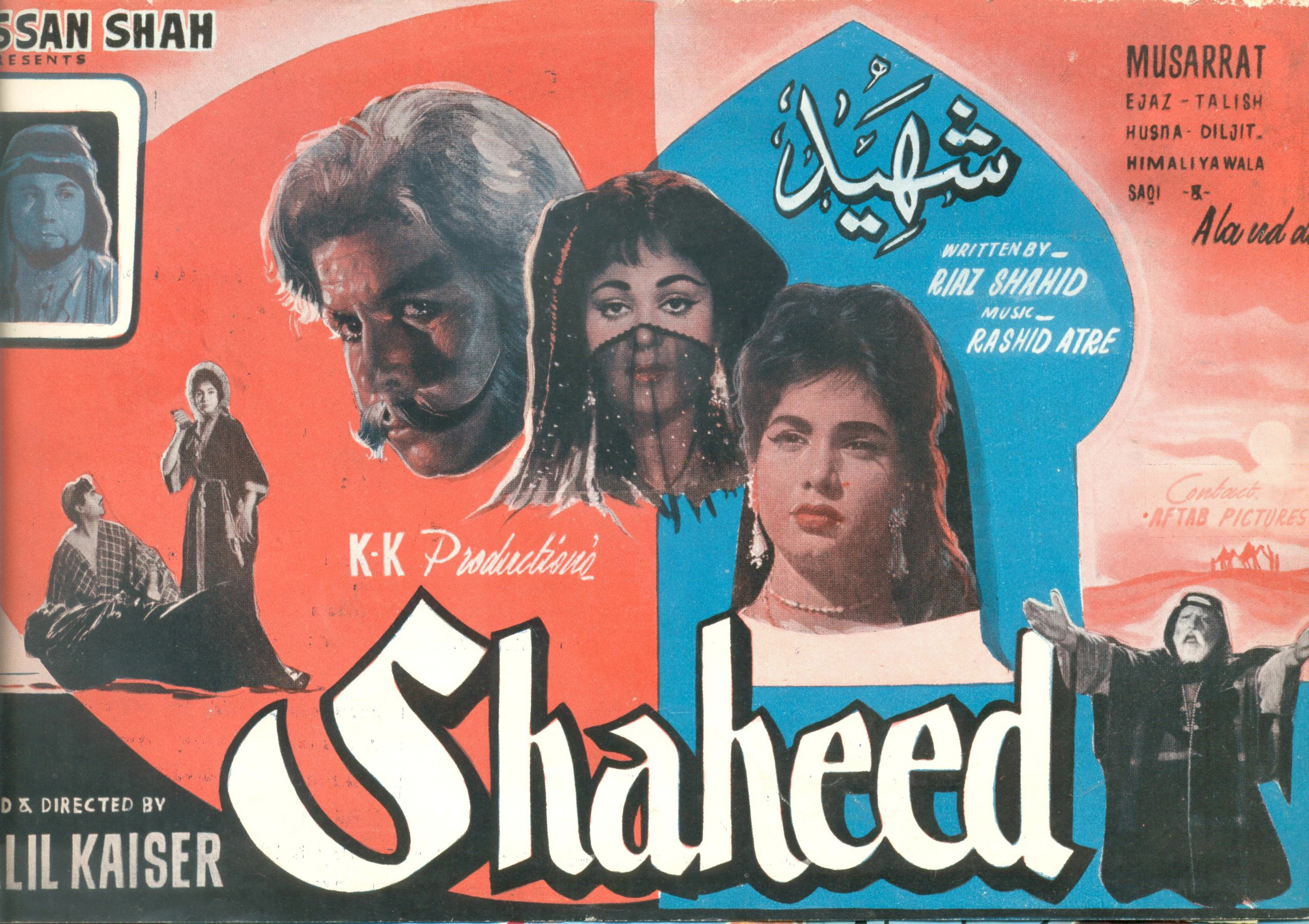

While teaching film studies at IQRA University in Lahore a number of years ago, a young student in the front of the class put up his hand and asked me a question. ‘Sir, all I want to do is make Pakistani version of The Matrix.’ While applauding his ambition, I could not help thinking his sights were set a little high. Not being one to douse enthusiasm and well aware that passion can build the seemingly impossible, I encouraged him to keep his dream alive. After all, in the 1950s to 1970s when his father was young, Lahore was blockbuster capital.

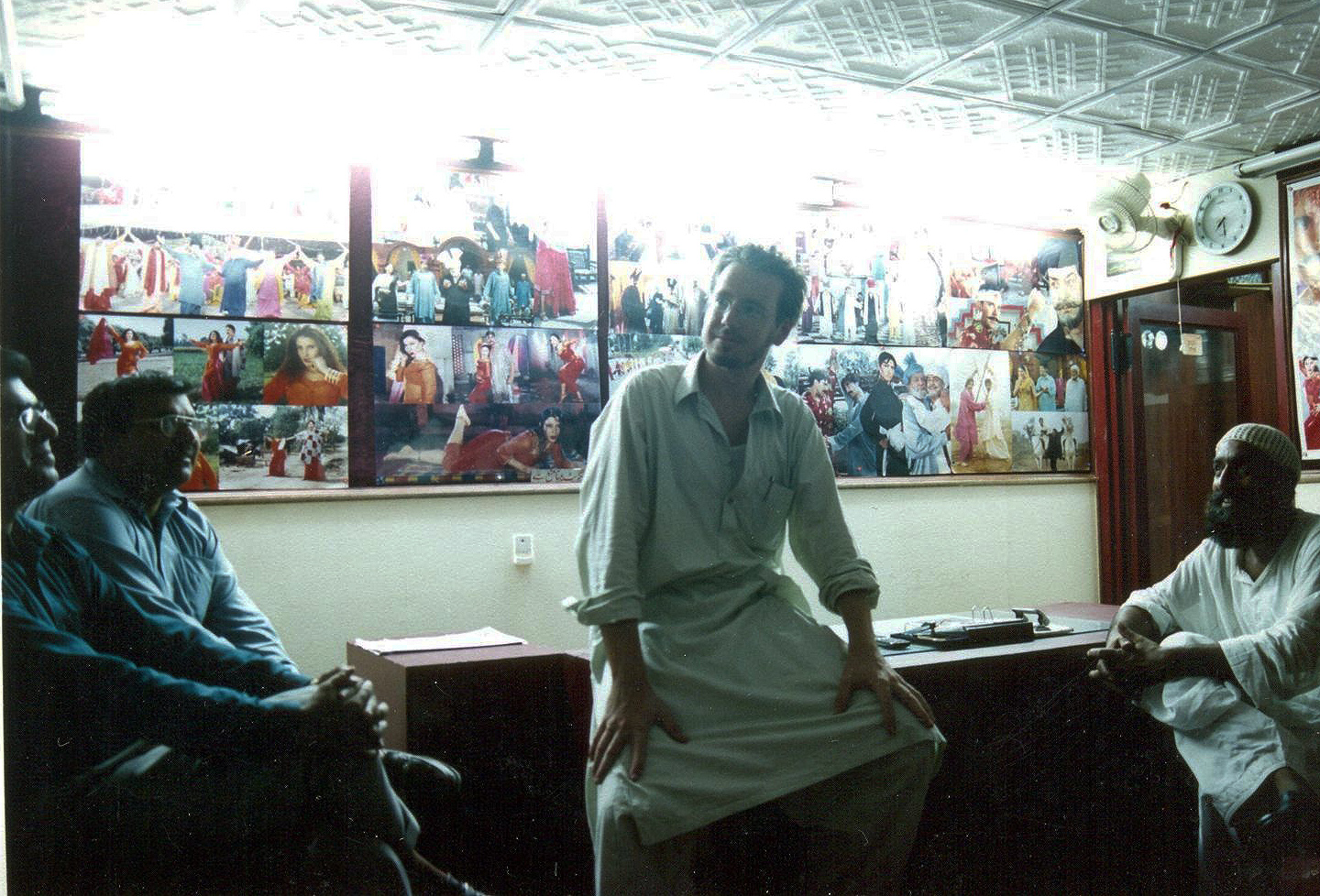

By 2004 however, the Pakistani film industry was a dilapidated house indeed, haunted by the memories of its golden years. My interest in Lollywood had taken me to Royal Park production offices, studios and film sets. Long conversations were held with depressed directors and cinematographers, heroes and villains.

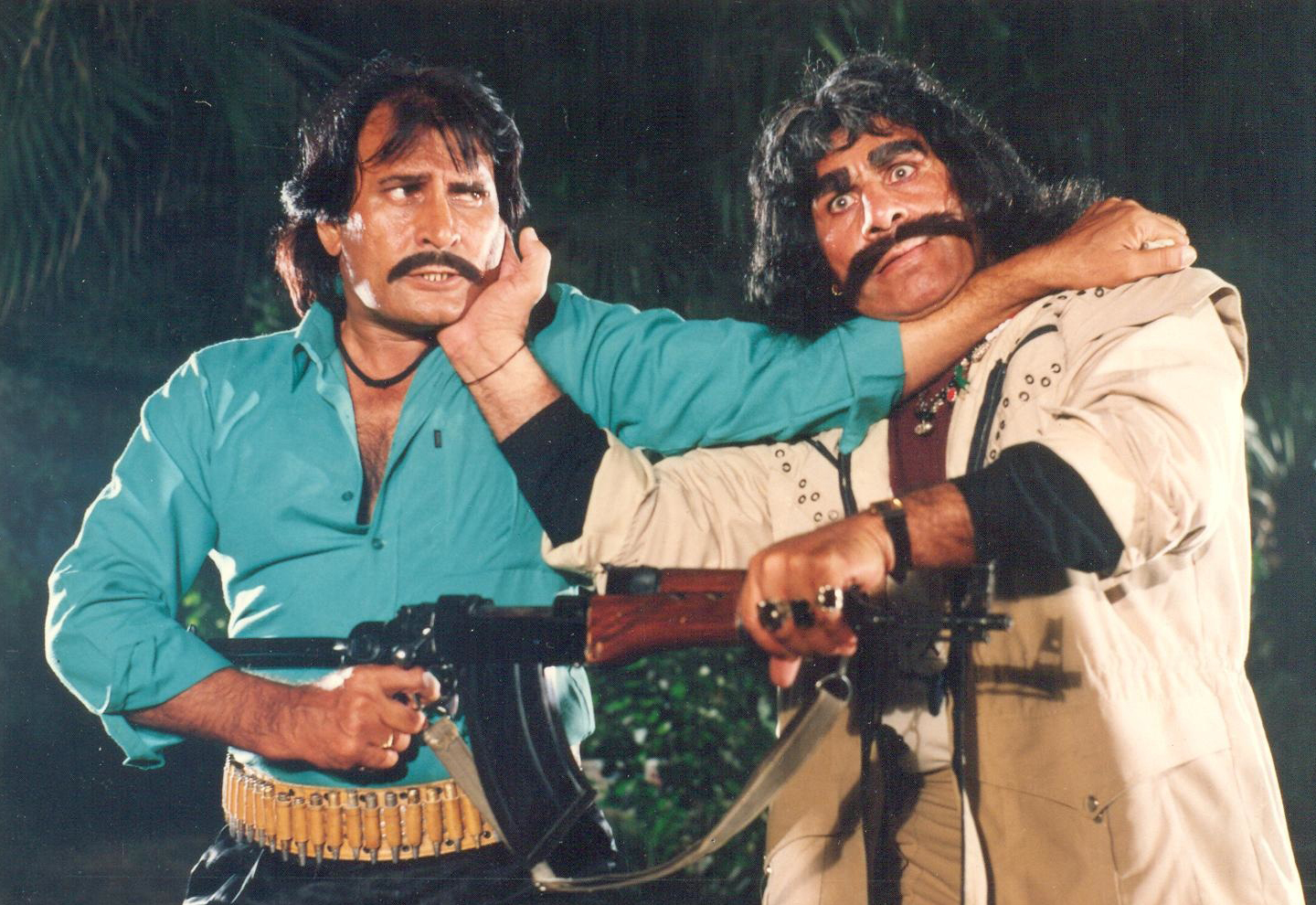

Sure, the industry was still making a handful of features for local audiences. But according to cinema owners audiences were very thin on the ground, the demographic narrow and common. Twenty-minute long AK47 shoot-outs, screaming eunuchs and buckets of chilli-sauce was not a recipe that appealed to the educated classes with finer taste. Women, couples, families and children had not been seen attending local films since the days before Zia Al Haq.

Ah, that name. Be it with filmmaker or film buff, almost every conversation I had on Lollywood ended in a tirade against the former President and his vision for a culturally-bland Islamist utopia. Indeed, his opinion on film was akin to some extremist views of today who mistakenly judge the medium rather than the content – a kind-of ‘shoot the messenger’ doctrine. His ban of male and female interaction on screen and other religious based policies affecting creative storytelling rapidly asphyxiated the industry. Video, cable and DVD was the final match that lit the pyre.

According to Alex Rodriquez of the LA Times, even as recently as last year Lahore’s Odean Cinema was still showing ‘Majajan’ as it had been, laboriously, for three years straight. At least it wasn’t inter-cut with ‘blue movie clips’ to keep the rickshaw drivers happy – a draw card of some suburban movie houses barely able to keep their heads above water. No wonder the Taliban threw a grenade down the isle in the Kohat Cinema last year, resulting in its eventual demolition. In 1985, 1,100 cinemas operated in Pakistan, now fewer than 100 open their doors.

So then, what’s all this buzz about Pakistan’s ‘New Cinema Movement’?

The internet and print media has been recently flooded with excitement about an emergence from a cultural drought, that something happened in 2009, a light of some kind, a fragrant whiff perhaps, of a Pakistani renaissance in film. Surprising it would be too, given that state-sponsored extremism has escaped from its leash. How can we realistically claim there is a cultural revolution beginning in a country beset by suicide bombings, a country where threats to artists, musicians and filmmakers in some provinces has left them paralyzed with fear? Filmmakers in Peshawar these days are struggling as the only films the Taliban seem to condone feature beheadings. Not that I blame the extremists alone for this state of affairs, their work is recognized internationally as supported by various players with a stake in the Great Game: Part 2.

All this could serve to refute any suggestion of a cultural renaissance. And yet the opposite is true. Having re-visited all major cities in Pakistan last month, it is my overwhelming impression that the current geopolitical mess and the attempted suffocation of cultural vestiges by extremist groups will succeed only in creating a backlash among a population thirsty for self-expression. While some segments of the society have clearly been radicalized, this will not be sustained in the long term. Already the US and NATO are winding down in Afghanistan which will, sooner than later, bring an end to the Af/Pak conflict. Even the Pashtuns and Baluchis, assumed by many other ethnic groups to have embraced extremism far too readily over the past three decades, have largely done so for the purpose of motivation and unification in their rebellion against imperial interference, be it Soviet or American. Once the US pressure on Pakistan abates, army units pull out of FATA and conservative groups are included in the political process, extremism too will rapidly wane, leaving room for a cultural revolution to also flourish in the Western regions of the country. It is well worth remembering the Renaissance in Europe arose from the darkest years of the Middle Ages, a period characterized by the negative social factors of poverty, warfare, religious and political persecution. As Pakistan is currently beset with similar problems, one could well argue that the environment for a revolution is ripe.

Risks involved in making and releasing films in the present conditions that exist in Pakistan indicate the entrée of a cultural revolution seems to have started outside of the country. Expatriate filmmakers and their distributors in the US, Europe and UK have had terrific success in 2009 particularly with Pakistani films. Mara Pictures based in London, for example, have had a continuous slate of Pakistani films since their inception last year, all of which have played major festivals and succeeded at the box office. Some have suggested the recent Pakistani films released internationally are being made by the upper classes embarrassed by the negative stereotypes of Pakistan as a terrorist nation. My response to that is that Pakistanis of every class and cultural group are saddened by their mistaken identify. As director of a film featuring gun-wielding Pashtuns, I have been criticized by a few for my focus on FATA. On closer inspection of my film, however, those critics have come to realize that I have simply given voice to a minority who are fighting to preserve their traditional way of life. As Pakistani filmmakers bring a true picture of their identity to the world, they must also accept that this identity is far from singular. While Sindhi nomads amble across the Thar desert, Karachi advertising executives whoosh through peak-hour traffic, Kalash farmers tend their fruit trees and Pashtun tribesmen discuss property over tea, worried where the next US missile will strike. Pakistan has, quite obviously, millions of stories, each story an equally valuable thread of the nation’s fabric, desperate to reach the wider world.

More Pakistani youth are realizing that now is the time to shape both their country and their country’s image. Instead of barracking for the counter-insurgency that has simply inflamed and compounded instability, many Pakistanis are making it their priority instead to reject the disease of corruption, to seek justice, reduce poverty, promote education and reinvigorate their cultural tapestry. What does the world think these days when it hears the word Pakistan? War? Terrorism? Extremism? So many people tragically and mistakenly do, ignorant of the country’s rich history in music, poetry and Sufism.

Now is the time for Pakistanis to be masters of their own identity. And what better way to do this than with the medium of film.